Originally called Armistice Day, this day’s history truly began on November 4th, 1918, when the German government began putting feelers out to see if a World War I ceasefire with the Allies was possible. There had been uneasiness in the ranks since President Wilson’s controversial “Fourteen Points” plan for peace was announced in January 1918, and now the Germans were considering their options.

By November 6th, 1918, the reality of a true “armistice” began materializing amid the leaders of an exhausted Germany ready to call a truce. Continued loss of support, threats of revolution, and political turmoil finalized their decision, resulting in a scheduled end to the hostilities and the sudden abdication of Germany’s last Kaiser, Kaiser Wilhelm II.

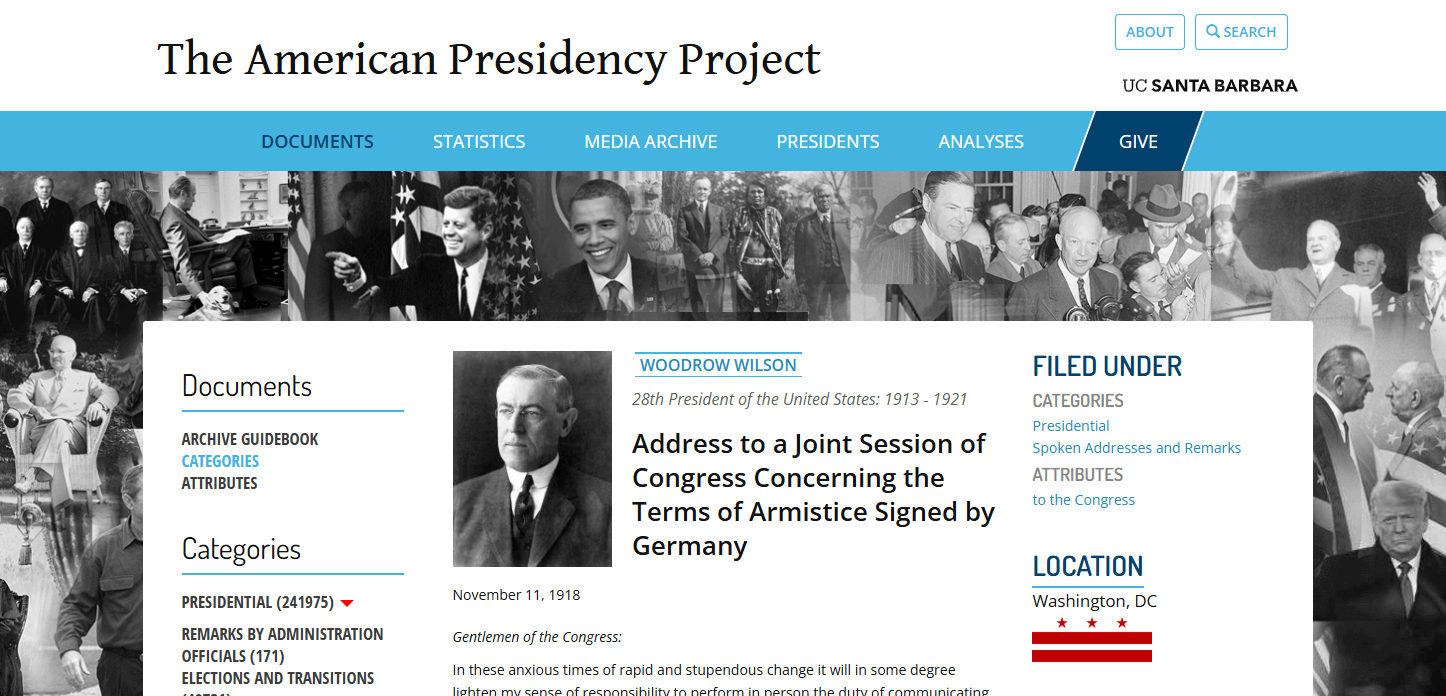

The eleventh day of the eleventh month arrived, and at 11 a.m. “the war to end all wars” ended in agreement and President Wilson informed Congress the terms of the armistice had been accepted and acted upon. Robert Casey, Battery C, 124th Field Artillery Regiment, 33rd Division, described it this way:

“And this is the end of it. In three hours, the war will be over. It seems incredible even as I write it. I suppose I ought to be thrilled and cheering. Instead, I am merely apathetic and incredulous . . . there is some cheering across the river-occasional bursts of it as the news is carried to the advanced lines. For the most part, though, we are in silence . . . with all is a feeling that it can’t be true. For months we have slept under the guns . . . we cannot comprehend the stillness.”

One year later, President Wilson’s radio address proclaimed the first Armistice Day with the following words:

“To us in America, the reflections of Armistice Day will be filled with solemn pride in the heroism of those who died in the country’s service and with gratitude for the victory, both because of the thing from which it has freed us and because of the opportunity it has given America to show her sympathy with peace and justice in the councils of the nations . . . “

The celebration began with a public suspension of business marking the 11 a.m. memorial for two minutes. As time went on, the ceremonial recognition grew to include a 1921 burial of an unknown soldier in Arlington National Cemetery, a 1926 Congressional resolution formally naming the day of honor, and the 1938 Congressional action to declare it a national holiday.

The onset of World War II delivered the realization that peace was fragile and political promises could be shattered. The celebration of peace drifted away during the next six years of reports from war. A weary nation welcomed their warriors home in 1945, reigniting the understanding that our country’s list of those who had served could continue to grow in a world full of troubles.

As the temporary nature of peace and true armistice weighed upon the battle-worn minds of Americans, a WWII veteran named Raymond Weeks decided to launch the first event labeled with National Veterans Day. This parade through the streets of Birmingham first took place on November 11th, 1947. His action of honor for those who served was echoed by President Eisenhower and Congress in 1954, as they passed a bill that changed the name of the November 11th day of peace to Veterans Day. The launch of that Birmingham parade would also earn Weeks a Presidential Citizens Medal thirty-five years later.

With the exception of one ten-year period, from 1968 to 1978, during which Congress changed the recognized date to the fourth Monday in October, we have been honoring the men and women paving the way for our freedom on November 11th for over seventy years. What was borne of an agreement of peace became respect for those fighting to maintain it, and war after war has facilitated its necessity. Thank you will never be enough to overcome the reasons this day exists, but it is the bare minimum that should be granted to those who have granted so much to us.

And I think there is another way we can demonstrate our appreciation—by living our lives cherishing the opportunity to act upon what they fought for. What if we honored others with the same determination they exhibited when defending our chance to do so?

That question becomes paramount as the world drifts further and further away from both the definition and the necessity of honor. Honor is not just a word to be repeated, it is a promise to be understood and acted upon. Veterans understand it is not a catch phrase, but a code they live by. What if we followed the example of their sacrifice even within our social media feeds, embracing honor and respect for each other as a way of life instead of just a remembrance? When you look back through history, there is account after account of heroic actions of respect even between opposing sides. Decisions for actions taken or withheld sparked by understanding and recognition that the man or woman on the other side of the fence was someone’s parent, someone’s child, someone’s person. It was an unspoken code that understood real honor was rooted in the humane treatment of one another, no matter what side we fought on.

I don’t think the world will ever change, but I believe we can. I believe each of us holds something valuable, something granted to us by those who cleared the way for our freedom, giving a sacrifice we could not give. Who are we really if we don’t give that honor back to someone else?

Shouldn’t we at least try to honor each other with the same code? Because right now, more than ever, staying in the trenches is hard. Surviving the onslaught of being someone’s target takes a toll on the mind and soul. The days feel like there is no end in sight and the nights are cries of exhaustion. And the one next to you feels the same, even if they don’t say it out loud. So, today, let us watch those who understand honor so we can understand honor. What we understand we can apply. What better way to honor those who led by example than to put into practice the lessons they taught? How can you honor someone today?